Author and Page information

Obesity is a growing global health problem. Obesity is when someone is so overweight that it is a threat to their health.

Obesity is a growing global health problem. Obesity is when someone is so overweight that it is a threat to their health.

Obesity typically results from over-eating (especially an unhealthy diet) and lack of enough exercise.

In our modern world with increasingly cheap, high calorie food (example, fast food — or junk food

), prepared foods that are high in things like salt, sugars or fat, combined with our increasingly sedentary lifestyles, increasing urbanization and changing modes of transportation, it is no wonder that obesity has rapidly increased in the last few decades, around the world.

Number of People Overweight or With Obesity Rivals World’s Hungry

In the poverty section primarily, but also in other parts of this web site, much has been written about the causes of hunger in the face of abundant food production due to things like land use, political and economic causes, etc. However, there is another side to this emerging as well: growing obesity. The World Watch Institute noted this quite a while ago and is worth quoting at length:

For the first time in human history, the number of overweight people rivals the number of underweight people.… While the world’s underfed population has declined slightly since 1980 to 1.1 billion, the number of overweight people has surged to 1.1 billion.

… the population of overweight people has expanded rapidly in recent decades, more than offsetting the health gains from the modest decline in hunger. In the United States, 55 percent of adults are overweight by international standards. A whopping 23 percent of American adults are considered obese. And the trend is spreading to children as well, with one in five American kids now classified as overweight.… [O]besity cost the United States 12 percent of the national health care budget in the late 1990s, $118 billion, more than double the $47 billion attributable to smoking.

… Overweight and obesity are advancing rapidly in the developing world as well … [while] 80 percent of the world’s hungry children live in countries with food surpluses.

… technofixes like liposuction or olestra attract more attention than the behavioral patterns like poor eating habits and sedentary lifestyles that underlie obesity. Liposuction is now the leading form of cosmetic surgery in the United States, for example, at 400,000 operations per year. While billions are spent on gimmicky diets and food advertising, far too little money is spent on nutrition education.

Chronic Hunger and Obesity Epidemic; Eroding Global Progress, World Watch Institute, March 4, 2000(Emphasis added)In the above, note also how many resources are wasted

or diverted to either deal with the ramifications (such as health costs), or to deal with the symptoms (via techniques such as liposuction). Of course, that is not to say that resources should not be spent on these things at all, but that it is far more cost effective and more desirable to treat the root causes, as treating symptoms only leaves underlying causes in tact.

This is an example of hidden

costs of consumption on top of the visible

costs. The World Watch Institute article, quoted above, goes on to further show that comparatively less expensive measures that deal with causes have been very effective at reducing obesity problems, such as teaching nutritional literacy in schools.

The BBC revealed that food wastage is enormous. In the United Kingdom, some astonishing 30-40% of all food is never eaten, while in the US, some 40-50% of all food ready for harvest never gets eaten. UK alone sees some £20 billion ($38 billion US dollars) worth of food thrown away each year. Furthermore, the additional rotting food creates methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

As people eat more and more health and safety of the food production process become more important, too. Nursing Schools lists a number of concerning facts about food in the US:

- 40-50% of all food ready for harvest never gets eaten.

- Every year, over 25% of Americans get sick from what they eat.

- As few as 13 major corporations control nearly all of the slaughterhouses in the U.S.

- Americans eat 31% more packaged food than fresh food.

- The FDA tests only about 1% of food imports. (The US imports about 15% of what they eat.)

- A simple frozen dinner can contains ingredients from over 500 different suppliers so you have to trust all of those hundreds of companies along the way stuck to regulations about food safety.

- 50% of tested samples of high fructose corn syrup tested for mercury.

- Americans eat about six to nine pounds of chemical food additives per year.

- Food intolerance is on the rise, with as many as 30 million people in the U.S. showing symptoms.

- Fewer than 27% of Americans eat the correct ratio of meats to vegetables.

- 80% of the food supply is the responsibility of the FDA yet the number of inspections has decreased while the number of producers has increased.

- Keeping fields contamination-free can cost well over $250,000–a discouraging sum to smaller farmers. Obesity on the Increase

The World Watch Institute’s statistics above are now over 8 years old but still useful for context.

The World Health Organization (WHO) provides a number of facts on obesity, including that globally in 2005:

- Approximately 1.6 billion adults (age 15+) were overweight

- At least 400 million adults were obese

- At least 20 million children under the age of 5 years are overweight globally in 2005.

The WHO also projected that by 2015, approximately 2.3 billion adults will be overweight and more than 700 million will be obese.

Childhood obesity is also an increasing concern for the WHO:

The problem [of childhood obesity] is global and is steadily affecting many low- and middle-income countries, particularly in urban settings.… Globally, in 2010 the number of overweight children under the age of five, is estimated to be over 42 million. Close to 35 million of these are living in developing countries.

Overweight and obese children are likely to stay obese into adulthood and more likely to develop noncommunicable diseases like diabetes and cardiovascular diseases at a younger age.

Childhood overweight and obesity, WHO, last accessed August 22, 2010Recent years have seen a large increase in those overweight or obese.

The WHO provides charts showing how the prevalence of those who are overweight or obese has increased between 2002 and 2010 for both males and females ovr 15:

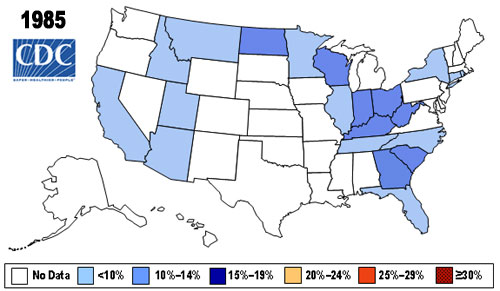

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the US provided a series of charts showing how obesity has dramatically increased amongst adults in the US from 1985-2008:

Percent of Obese (BMI > 30) in U.S. Adults in 1985

Percent of Obese (BMI > 30) in U.S. Adults in 1985(I have not found similar sources for other countries, yet. If you know, please let me know.)

Also note that the WHO figures above are using a body mass index of greater than or equal to 25 as it includes both overweight and obese. The CDC numbers for US states are obese numbers only.

Back to top

Obesity Affects Poor as well as Rich

Obesity also affects the poor as well, due to things like marketing of unhealthy foods as the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) highlights. Restrictions in access to food determine two simultaneous phenomena that are two sides of the same coin: poor people are malnourished because they do not have enough to feed themselves, and they are obese because they eat poorly, with an important energy imbalance… The food they can afford is often cheap, industrialized, mass produced, and inexpensive.

The WHO that many low- and middle-income countries are now facing a double burdern

of disease:

- While they continue to deal with the problems of infectious disease and under-nutrition, at the same time they are experiencing a rapid upsurge in chronic disease risk factors such as obesity and overweight, particularly in urban settings.

- It is not uncommon to find under-nutrition and obesity existing side-by-side within the same country, the same community and even within the same household.

- This double burden is caused by inadequate pre-natal, infant and young child nutrition followed by exposure to high-fat, energy-dense, micronutrient-poor foods and lack of physical activity.

Award-winning journalist Michael Pollan, commenting in an interview on the problem for America’s poor, notes that basic crops such as corn and soybeans are used to such an extent that many unhealthy and processed foods are created from them, at a subsidized rate, thus contributing to the problem:

Because we subsidize those calories, we end up with a supermarket in which the least healthy calories are the cheapest. And the most healthy calories are the most expensive. That, in the simplest terms, is the root of the obesity epidemic for the poor—because the obesity epidemic is really a class-based problem. It’s not an epidemic, really. The biggest prediction of obesity is income.

Blair Golson, America’s Eating Disorder, Alternet.org, April 19, 2006Pollan and bestseller Eric Schlosser also released a documentary film, Food Inc, that looks into the effects of subsidizing unhealthy practices, further. Schlosser’s bestselling book, Fast Food Nation is also discussed on this site’s section on beef.

Back to top

Health impacts

With obesity comes increasing risks of

- Cardiovascular disease (mainly heart disease and stroke) — already the world’s number one cause of death, killing 17 million people each year.

- Diabetes (type 2) — which has rapidly become a global epidemic.

- Musculoskeletal disorders — especially osteoarthritis.

- Some cancers (endometrial, breast, and colon).

In addition, childhood obesity is associated with a higher chance of premature death and disability in adulthood.

The WHO adds, What is not widely known is that the risk of health problems starts when someone is only very slightly overweight, and that the likelihood of problems increases as someone becomes more and more overweight. Many of these conditions cause long-term suffering for individuals and families. In addition, the costs for the health care system can be extremely high.

In Europe, for example, the WHO’s European regional body says that obesity is already responsible for 2-8% of health costs and 10-13% of deaths in different parts of the Region.

(See the obesity and overweight facts and What are the health consequences of being overweight?, both by the WHO, for more details.)

In Britain for example, a Centre for Food Policy and Thames Valley University report, titled Why health is the key for the future of farming and food (January 2002) says that despite food scandals getting headlines, far more people are affected by diet-related diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes and nutritional deficiencies than diarrhoeal diseases (salmonella, campylobacter, etc) — some 35% compared to 0.2%.

As the report says bluntly, food safety may scandalise the country and attract political attention, but it is the routine premature death by degenerative disease that extracts the greater ill-health toll

(p.15).

This phenomena is seen in many rich nations, though Britain comes out worse than most on many such indicators (p.16).

The report further highlights that the costs of coronary heart disease alone are around £10 billion a year (approximately 14 billion in U.S. dollars). These costs are made up of

- £1.6 billion in direct costs (primarily to the tax payer through the costs of treatment by the British National Health Service) and

- £8.4 billion in indirect costs (to industry and to society as a whole, though loss of productivity due to death and disability). (p. 38)

Other issues and problems they point out include:

- Encouraging/advertising unhealthy diets and foods (especially to children);

- Generally putting low priority on health;

- Industry-dominated food policy at the expense of local grocery stores;

- Deteriorating health of children in poverty;

- and so on.

The report however, does not include costs from the effects of wider industrial agricultural policies that have given rise to BSE, Foot and Mouth disease, or the cost to the environment, etc.

New York Times food writer Mark Bittman summarizes how this is a global issue because over-consumption and over-industrialized-production of unhealthy foods is also putting the entire planet at risk:

Experts believe that obesity is responsible for more ill health even than smoking, the BBC has noted, which ties in with the World Watch quotation above about health costs for obesity in the U.S. exceeding those associated with smoking.

Back to top

Various causes of obesity

Taking a more global view, the prestigious British Medical Journal (BMJ) looks at various attempts to tackle obesity and notes that obesity is caused by a complex and multitude of inter-related causes, fuelled by economic and psychosocial factors as well as increased availability of energy dense food and reduced physical activity.

The authors broke down the causes into the following areas:

- Food systems causes of obesity

The main problem has been the increased availability of high energy food, because of:

- Liberalized international food markets

- Food subsidies that

have arguably distorted the food supply in favour of less healthy foodstuffs

Transnational food companies [that] have flooded the global market with cheap to produce, energy dense, nutrient empty foods

Supermarkets and food service chains [that are] encouraging bulk purchases, convenience foods, and supersized portions

- Healthy eating often being more expensive than less healthy options, (despite global food prices having dropped on average).

- Marketing, especially

food advertising through television [which] aims to persuade individuals—particularly children—that they desire foods high in saturated fats, sugars, and salt.

- The local environment and obesity

How people live, what factors make them active or sedentary are also a factor. For exapmle,

Research, mainly in high income countries, indicates that local urban planning and design can influence weight in several ways.

- For example, levels of physical activity are affected by

- Connected streets and the ability to walk from place to place

- Provision of and access to local public facilities and spaces for recreation and play

- The increasing reliance on cars leads to physical inactivity, and while a long-time problem in rich countries, is a growing problem in developing countries.

- Social conditions and obesity

Examples of issues the BMJ noted here include

Working and living conditions, such as having enough money for a healthy standard of living, underpin compliance with national health guidelines

Increasingly less job control, security, flexibility of working hours, and access to paid family leave … undermining the material and psychosocial resources necessary for empowering individuals and communities to make healthy living choices.

- Inequality, which can lead to different groups being disadvantaged and having less access to needed resources and healthier foods

Back to top

Addressing Obesity Globally, Nationally, Locally, Individually

British celebrity-chef-turned-food-activist, Jamie Oliver, recently won the prestigious TED Prize for his campaigning in the UK to fight obesity. His wish

that the TED Prize speech asks him to share was to help to create a strong, sustainable movement to educate every child about food, inspire families to cook again and empower people everywhere to fight obesity.

He explained this in his video:

Given the complex, inter-related causes of obesity, addressing it also requires a multi-pronged approach:

Dealing with inequalities in obesity requires a different policy agenda from the one currently being promoted. Action is needed that is grounded in principles of health equity.

…

Missing in most obesity prevention strategies is the recognition that obesity—and its unequal distribution—is the consequence of a complex system that is shaped by how society organises its affairs. Action must tackle the inequities in this system, aiming to ensure an equitable distribution of ample and nutritious global and national food supplies; built environments that lend themselves to easy access and uptake of healthier options by all; and living and working conditions that produce more equal material and psychosocial resources between and within social groups. This will require action at global, national, and local levels.

Sharon Friel, Mickey Chopra, David Satcher, Unequal weight: equity oriented policy responses to the global obesity epidemic, British Medical Journal, Volume 335, December 15, 2007, pp. 1241-1243The BMJ criticizes traditional methods to address obesity as typically trying to change individual’s behavior. While important, on its own, they feel it is not sufficient; there is limited evidence for sustainability [of this direct approach] and transferability to other settings,

for example.

Furthermore, the recent UK Foresight Report makes clear the complexity of drivers that produce obesity; it highlights that most are societal issues and therefore require societal responses.

The BMJ therefore describes some examples of initiatives at these various levels:

- Addressing obesity at the global level

This involves international institutions, agreements, trade and other policies. For example,

- The World Health Organization (WHO) is a key institution at this level. It’s global strategy in this area focuses on developing food and agricultural policies that are aligned to promoting public health and multisectorial policies that promote physical activity, as well as generally being an information provider.

- A joint program of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization, the experience of the Codex Alimentarius Commission highlights the challenges at international level. The Commission was set up to help governments protect the health of consumers and ensure fair trade practices in the food trade.

- But challenges and obstacles persist. For example,

industry representatives hugely outnumber representatives from public interest groups, resulting in an imbalance between the goals of trade and consumer protection.

In addition,

Ensuring that global food marketing does not target vulnerable societies

the BMJ feels there needs to be binding international codes of practice related to production and marketing of healthy food, supported at the national level by policy and regulation.

- This is preferred over voluntary guidelines, typical of the industry’s response to threats of regulation, because such responses

may result in differential uptake by better-off individuals or institutions and provides little opportunity for public and private sector accountability.

(Emphasis added) - For example,

regulating television advertising of foods high in fat or sugar to children is a highly cost effective upstream intervention.

(This is also discussed in more detail on this site’s section on Children as Consumers.)

- Addressing obesity at the national level

National policies typically aimed at healthier food production include targeted and appropriate domestic subsidies. For example,

Norway successfully reversed the population shift towards high fat, energy dense diets by using a combination of food subsidies, price manipulation, retail regulations, clear nutrition labelling, and public education focused on individuals.

- Mauritius relatively successful program includes price policy, agricultural policy, and widespread educational activity in various settings.

Ireland is an example of the also-needed multi-agency approach with their Healthy Food for All initiative seeking to promote access, availability, and affordability of healthy food for low income groups.

- Addressing obesity at the local level

Examples of local level action the BMJ mentioned include

- The success of the Brazilian population-wide Agita Sao Paulo physical activity program which

successfully reduced the level of physical inactivity in the general population by using a multi-strategy approach of building pathways; widening paths and removing obstacles; building walking or running tracks with shadow and hydration points; maintaining green areas and leisure spaces; having bicycle storage close to public transport stations and at entrances of schools and workplaces; and implementing private and public incentive policies for mass active transport.

- The London Development Agency plans to establish a sustainable food distribution hub to supply independent food retailers and restaurants.

However, a key challenge they note is the lack of systematic evaluation of initiatives, particularly with an equity focus, [which] makes it difficult to generalize policy solutions in this field.

So while there are many measures possible at many levels, a cultural shift in attitude is needed.

The benefits of a healthier diet is obvious. Yet, as Dr. Dean Ornish, a clinical professor and founder of the Preventive Medicine Research Institute, explains, the large number of cardiovascular diseases that kill so many around the world is not only preventable, but reversible, often by simply changing our diets and lifestyle:

Dean Ornish on the world’s killer diet, TED Talks, December 2006Another BMJ article notes in a prognosis in obesity that we need to move a little more and eat a little less:

New economic analyses help dispel the myth of people getting fatter but eating less. The first 20 years of our adult obesity epidemic, from the 1970s to 1990s, was explained mainly by declining physical activity: Americans believe they have less time to do things but in reality are spending more time watching television and being inactive. Subsequently, the obesity epidemic appears to have been fuelled by largely increased food consumption. A paradoxical increase and deregulation of appetite during inactivity has been matched by an increasing supply of food at lower real cost. Consumption of supersize

food portions will accelerate this process, reflecting a failure of the free market that demands government intervention.

Professor M E J Lean, Prognosis in obesity; we all need to move a little more, eat a little less, British Medical Journal, Volume 330, 11 June 2005, p.1339Award-winning journalist Michael Pollan argues in an interview that not only is what you eat important, but how you eat, as well:

At the end of the industrial food chain, you need an industrial eater. What you eat, and how you eat are equally important issues. There is a lot of talk and interesting comparisons drawn between us and the French on the subject of food. We’re kind of mystified that they can eat such seemingly toxic substances—triple crème cheeses and foie gras, and they're actually healthier than we are.

They live a little bit longer, they have less obesity, less heart disease. What gives? Well, according to the people who study this: It’s not what they eat, it’s how they eat it. They eat smaller portions; they do not snack as a rule; they do not eat alone. When you eat alone, you tend to eat more. When you’re eating with someone there’s a conversation going on, there’s a sense of propriety; you don’t pig out when you’re eating at a table with other people.

So the French show you can eat just about whatever you want, as long as you do it in moderation. That strikes me as a liberating message. But it’s not the way we do things here. We have a food system here that is all about quantity, rather than quality. So how you eat is very, very important, and to solve the obesity and the diabetes issue in this country, we’re going to have change the way we eat, as well as what we eat.

Blair Golson, America’s Eating Disorder, Alternet.org, April 19, 2006Perhaps a more bizarre suggestion in UK has been by a doctor (or scientist — I heard this on the radio and did not have time to get the exact details) who suggested that McDonald’s should narrow their doors so that fat people cannot get in. Maybe this hints at how extreme the problem might be for a medical doctor to be so extreme in a possible solution, as there are problems with this type of suggestion. For example,

- This sounds like an extremist and reactionary measure to deal with the issue, and raises concerns about rights of individuals to make their own choices.

- Furthermore, it could lead to a form of prejudice and hostility towards certain types of people.

- More effective could be to address the deeper issues discussed further above and below.

- For example, the fast food industry is not effectively charged for their contribution to environmental destruction around the world, or even their indirect contribution to world hunger by making poor people grow food for export rather than to feed themselves. (See this site’s section on beef, and hunger for more on these aspects.)

- These examples just touch the surface, but these all add up to hidden costs for society but savings for the fast food companies.

- Pricing beef, for example, based on true cost of production would make these inefficient and unhealthy foods more expensive, and a deterrent for the majority of people, who might turn to healthier options (though this itself isn’t an automatic given).

But the underlying concern of the doctor is still important. At the end of April 2004, the British government urged the public to exercise five times a week. Levels of physical activity among the general population have fallen significantly over the past 25 years the government had also noted. Compelling scientific evidence shows that more active people are less likely to become obese and develop heart disease.

Another major determinant in people’s preferences and habits, especially in a consumer society, is marketing.

Back to top

Healthy versus Unhealthy Food Marketing; Who Usually Wins?

Of course, obesity is not an easy challenge to overcome, as today’s commercial markets include a very wide variety of foods that are unhealthy, but attractively marketed to kids, as also mentioned in the children section. And many resources are deployed to support that industry. This is another example of hidden waste

.

Soaring diabetes rates are inextricably tied to the global obesity epidemic, as Inter Press Service (IPS) notes. Yet, the political will to be able to change certain cultural habits and to take on powerful industries promoting such habits that lead to these problems, is where the challenge lies.

In theory were it not for these political and cultural challenges, the cost of addressing the problem could be quite low (regular exercise, sensible eating habits, for example). But, There is not enough resolve to take on these monster industries and to force changes that will make our environment promote healthy rather than unhealthy choices when it comes to food and physical activity

says Dr. David Schlundt, a psychology professor at the Diabetes Center of Vanderbilt University in Tennessee state, in that IPS article.

The WHO [World Health Organisation] is basically powerless to do anything about the problem other than draw attention to it and perhaps develop some recommendations that will be very difficult for governments to implement

Schlundt also notes.

Talk of banning ads to kids met with resistance from industry

As a small example, in November 2003, another UK government member of Parliament had suggested a bill to ban TV ads promoting food and drink high in fat, salt and sugar aimed at young children. This received a lot of support as well, as groups and other members of Parliament felt that self-governing by the industry was not working. However, the bill didn’t get anywhere due to lack of time although it is repeatedly being called for.

The BBC noted in March 2004 that over 100 of the UK’s leading health and consumer groups have urged the government to ban junk food ads, saying they are fueling rising rates of obesity.

Some of these groups are leading medical and related organizations in Britain.

However, as the BBC also noted, a UK government minister said she was skeptical about the merits of banning junk food ads and, in concert with what the food and drink industry said, sound science

was needed to ensure that this was indeed a major cause of health problems. Encouraging healthier living and eating would be better it was noted.

Ironically, it is the food and drink industry that has the advertising muscle and clout, and, as a campaigner from one of the groups commented, Huge profits are at stake, so we don’t believe that they will voluntarily stop promoting junk foods to kids. For the sake of children’s health, statutory controls are urgently required.

As also mentioned on this site’s section on Children as Consumers, industry raises fears that ad bans will result in job losses, but also a loss in quality programming for children, because those ads fund programs.

Industry attempts at self-regulation not working, sometimes reversing

Many groups have long been raising urgent concerns because a conservative estimate from experts suggests that over 40% of the UK population could become obese within a generation. The food and drink industry are on the defensive because of the potential loss in sales. As a result, they tend to suggest blaming the individual; it is the individual’s choice at the end of the day. However, while true, advertising is so much part of culture that it would be overly simplistic to say ads do not have an effect and that it is only through exercise and personal discipline that these issues can be overcome. Furthermore, if it is individual choice, then food companies would not need to market and create perceived food needs; the necessity to eat would be enough to drive the market.

The above example about pressure to ban advertising and the associated skepticism on its merits comes from the UK. In the US, industry has offered to self regulate. However, it looks as though pledges to reduce junk food advertising have not been met:

As detailed further on this site’s section on children and consumption, a number of food companies in the US said they would volunteer to cut ads directed towards children, as reported by the International Herald Tribune (December 11, 2007). The companies, Coca-Cola, Groupe Danone, Burger King, General Mills, Kellogg, Kraft Foods, Mars, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Ferrero and Unilever, agreed not to advertise food and beverages on television programs, Web sites or in print media where children under age 12 could be considered a target audience, except for products that met specific nutrition criteria.

However, 3 years on from the above announcement, The Food Advertising to Children and Teens Score (FACTS) — an organization developed by Yale University’s Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity to scientifically measure food marketing to youth — found that some of the pledges to reduce marketing had actually reversed.

It found that the fast food industry continues to relentlessly market to youth.

For example,

- The average preschooler (2-5) sees almost three ads per day for fast food; children (6-11) see three-and-a-half; and teens see almost five.

- Children’s exposure to fast food TV ads is increasing, even for ads from companies who have pledged to reduce unhealthy marketing to children.

- Children see more than just ads intended for kids. More than 60% of fast food ads viewed by children (2-11) were for foods other than kids’ meals.

Some $4.2 billion was spent in 2009, a fifth of which was by McDonald’s alone. TV accounted for the bulk of the advertising (86%) though Internet marketing was increasing. (See p.51 of their main report, Evaluating Fast Food Nutrition and Marketing to Youth (November 2010), for the details)

The organization suggested changing the industry-defined definition of television programs that require restrictions on the type of advertising aimed at children. Rather than restrictions only applying when the program is created solely for children, it wants a broader standard, such as the total number of children that watch a program. That would extend the reach of child friendly advertising guidelines to such broadly popular shows as American Idol and Glee. (See p.14 of the report)

Taxing junk food; a popular idea, but realistic?

If media regulation is proving challenging, then other ideas may too, such as some notion of tax on junk foods. The industry will of course be against such measures, instead preferring things like exercise and individual responsibility instead (though an individual — often poor on time — versus professional marketing usually suggests an imbalance in available information and decision-making).

Some studies suggest that economic instruments (such as price rises or taxation) of unhealthy foods might have an effect, but it is not guaranteed. For example,

This review found no direct scientific evidence of a causal relationship between policy-related economic instruments and food consumption, including foods high in saturated fats. Indirect evidence suggests that such a causal relationship is plausible, though it remains to be demonstrated by rigorous studies in community settings.

C. Goodman, A. Anise, What is known about the effectiveness of economic instruments to reduce consumption of foods high in saturated fats and other energy-dense foods for preventing and treating obesity?, Health Evidence Network, World Health Organisation, July 2006In mid-November, 2010, the BBC’s Panorama explored this notion of taxing the fat

, saying that Britain is the fattest nation in Europe, and wondered whether it was time to consider such a tax as it may help the National Health Service afford the various costs associated with this problem.

The documentary also went to Denmark — the first country in the world to implement such a tax — to see how it was working there, and to the US, where it explained how a proposal to tax sugary drinks like Coca Cola has met with fierce opposition.

It found that there were signs of young people losing weight in the already heavily taxed Denmark, although older adults were still gaining weight.

One potential use of the tax would be to subsidize healthier foods such as fruits and vegetables. But, a potential problem with taxing junk food is that many fruits and other healthy ingredients are often used in unhealthy foods such as sweets and sugary drinks, and even cosmetics and other products such as shampoos. So how can you ensure the tax proceeds are used appropriately?)

The documentary also implied that the current UK Health Secretary wasn’t keen on the idea and that his view was in line with the fast food industry, as targets and other measures may be lowered, as well as funding for current health campaigns for more active lives.

Exercise and individual responsibility has been the food industry’s preferred alternative to regulation (it avoids extra costs on the industry, which industry representatives claim would cost jobs and competitiveness, and while it transfers extra burden and cost onto consumers, they are often ready to sell more in relation to that as described further below).

However, the documentary also noted that more and more studies are showing that while both diet and exercise are crucial to healthy lives, the balance isn’t necessarily 50-50. Instead, diet appears to have a much larger bearing on people’s health and obesity. In addition, the numerous amounts of calories now available in fast foods are so high that the levels of exercise needed to burn the excess off is immense. Many people wouldn’t have that time.

And possibly as an example of a more bizarre sounding use of resources to get children to become more active, in Britain, a chocolate company was promoting sports equipment in return for vouchers and coupons from chocolate bars. The more you ate, the more sports equipment you would get, presumably to burn off the excesses eaten! The UK’s Food Commission called this absurd and contradictory

and pointed out that if children consumed all the promotional chocolate bars they would eat nearly two million kilos of fat and more than 36 billion calories.

The BBC, reporting on this (April 29, 2003), commented the following, amongst other things:

- One set of posts and nets for volleyball would require tokens from 5,440 bars of chocolate

- This would require spending £2,000 (about $3,500) on chocolate and wolfing their way through 1.25 million calories, some 2 million kilos of fat.

- A basketball would be 170 bars of chocolate, which, if it were to be burned off, a 10-year-old child would need to play for 90 hours.

While the confectionary companies suggested that children were going to eat these anyway, others raised concerns that this is promoting more unhealthy eating. The chairman of the UK government’s obesity task force, Professor Phil James, said: This is a classic example of how the food and soft drink industry are failing to take on board that they are major contributors to obesity problems throughout the world. They always try to divert attention to physical activity.

What is more, as most British media outlets also highlighted, then Minister for Sport, Richard Caborn, endorsed it.

But this is not the only example. For years, other companies have linked their foods to such schemes for educational or sports equipment for schools. What they get for selling this is branding and future consumers.

This has also been an example of controversial school commercialization which was unanimously condemned at a large teachers union conference in England around the same time.

This site’s section on Children as Consumers also notes that towards the end of 2007, additional efforts started in the UK to understand the effect of advertising on children. It also has more details on efforts to address issues related to obesity and the challenge parents (often the ones who are blamed) when going up against marketers. This is another example of how this can have all sorts of knock-on effects to society and to resource requirements to deal with these issues. And that results in further expenditure and use of resources which, from this perspective, can be seen as costly and wasteful.